Understanding Returns

Vexchange incentivizes users to add liquidity to trading pools by rewarding providers with the fees generated when other users trade with those pools. Market making, in general, is a complex activity. There is a risk of losing money during large and sustained movement in the underlying asset price compared to simply holding an asset.

Risks

To understand the risks associated with providing liquidity you can read https://medium.com/@pintail/Vexchange-a-good-deal-for-liquidity-providers-104c0b6816f2 to get an in-depth look at how to conceptualize a liquidity position.

Example from the article

Consider the case where a liquidity provider adds 10,000 VTHO and 100 WVET to a pool (for a total value of $20,000), the liquidity pool is now 100,000 VTHO and 1,000 VET in total. Because the amount supplied is equal to 10% of the total liquidity, the contract mints and sends the market maker “liquidity tokens” which entitle them to 10% of the liquidity available in the pool. These are not speculative tokens to be traded. They are merely an accounting or bookkeeping tool to keep track of how much the liquidity providers are owed. If others subsequently add/withdraw coins, new liquidity tokens are minted/burned such that everyone’s relative percentage share of the liquidity pool remains the same.

Now let’s assume the price trades on Coinbase from $100 to $150. The Vexchange contract should reflect this change as well after some arbitrage. Traders will add VTHO and remove VET until the new ratio is now 150:1.

What happens to the liquidity provider? The contract reflects something closer to 122,400 VTHO and 817 VET (to check these numbers are accurate, 122,400 * 817 = 100,000,000 (our constant product) and 122,400 / 817 = 150, our new price). Withdrawing the 10% that we are entitled to would now yield 12,240 VTHO and 81.7 VET. The total market value here is $24,500. Roughly $500 worth of profit was missed out on as a result of the market making.

Obviously no one wants to provide liquidity out of charitable means, and the revenue isn’t dependent on the ability to flip out of good trades (there is no flipping). Instead, 0.3% of all trade volume is distributed proportionally to all liquidity providers. By default, these fees are put back into the liquidity pool, but can be collected any time. It’s difficult to know what the trade-off is between revenues from fees and losses from directional movements without knowing the amount of in-between trades. The more chop and back and forth, the better.

Why is my liquidity worth less than I put in?

To understand why the value of a liquidity provider’s stake can go down despite income from fees, we need to look a bit more closely at the formula used by Vexchange to govern trading. The formula really is very simple. If we neglect trading fees, we have the following:

eth_liquidity_pool * token_liquidity_pool = constant_productIn other words, the number of tokens a trader receives for their VET and vice versa is calculated such that after the trade, the product of the two liquidity pools is the same as it was before the trade. The consequence of this formula is that for trades which are very small in value compared to the size of the liquidity pool we have:

eth_price = token_liquidity_pool / eth_liquidity_poolCombining these two equations, we can work out the size of each liquidity pool at any given price, assuming constant total liquidity:

eth_liquidity_pool = sqrt(constant_product / eth_price)token_liquidity_pool = sqrt(constant_product * eth_price)So let’s look at the impact of a price change on a liquidity provider. To keep things simple, let’s imagine our liquidity provider supplies 1 VET and 100 VTHO to the Vexchange VTHO exchange, giving them 1% of a liquidity pool which contains 100 VET and 10,000 VTHO. This implies a price of 1 VET = 100 VTHO. Still neglecting fees, let’s imagine that after some trading, the price has changed; 1 VET is now worth 120 VTHO. What is the new value of the liquidity provider’s stake? Plugging the numbers into the formulae above, we have:

eth_liquidity_pool = 91.2871dai_liquidity_pool = 10954.4511“Since our liquidity provider has 1% of the liquidity tokens, this means they can now claim 0.9129 VET and 109.54 VTHO from the liquidity pool. But since VTHO is approximately equivalent to USD, we might prefer to convert the entire amount into VTHO to understand the overall impact of the price change. At the current price then, our liquidity is worth a total of 219.09 VTHO. What if the liquidity provider had just held onto their original 1 VET and 100 VTHO? Well, now we can easily see that, at the new price, the total value would be 220 VTHO. So our liquidity provider lost out by 0.91 VTHO by providing liquidity to Vexchange instead of just holding onto their initial VET and VTHO.”

“Of course, if the price were to return to the same value as when the liquidity provider added their liquidity, this loss would disappear. For this reason, we can call it an impermanent loss. Using the equations above, we can derive a formula for the size of the impermanent loss in terms of the price ratio between when liquidity was supplied and now. We get the following:”

”

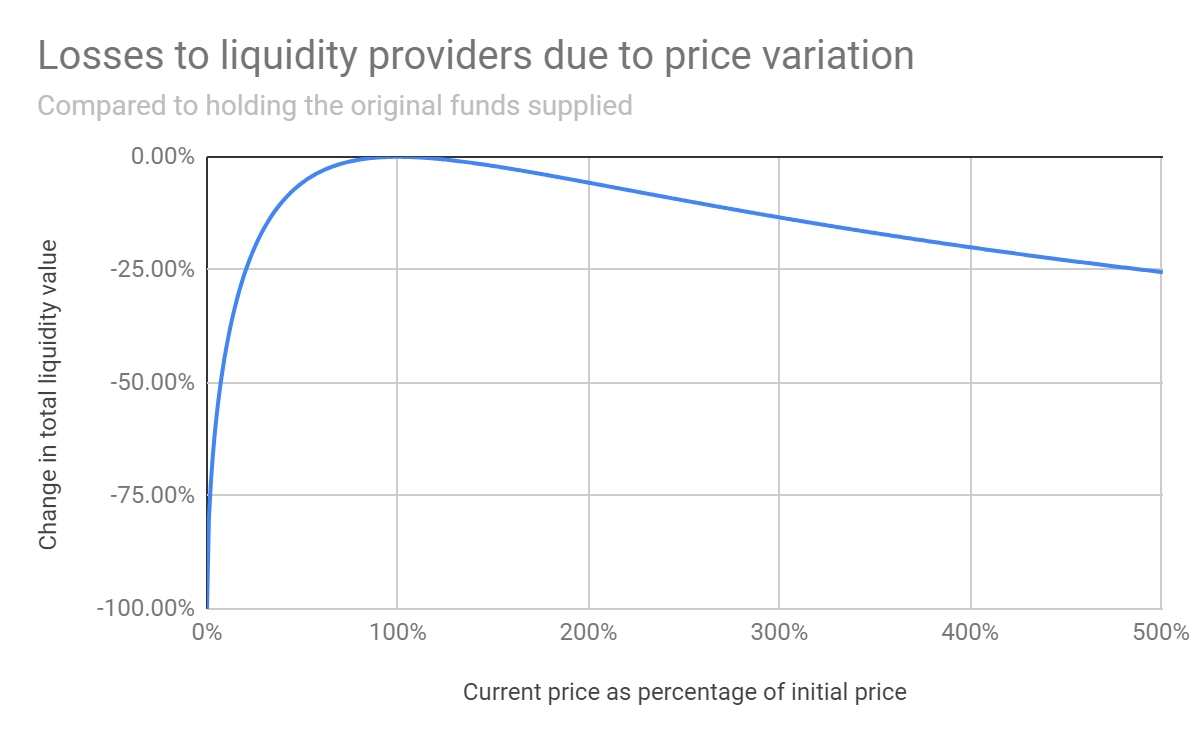

impermanent_loss = 2 * sqrt(price_ratio) / (1+price_ratio) — 1”“Which we can plot out to get a general sense of the scale of the impermanent loss at different price ratios:”

“Or to put it another way:”

- “a 1.25x price change results in a 0.6% loss relative to HODL”

- “a 1.50x price change results in a 2.0% loss relative to HODL”

- “a 1.75x price change results in a 3.8% loss relative to HODL”

- “a 2x price change results in a 5.7% loss relative to HODL”

- “a 3x price change results in a 13.4% loss relative to HODL”

- “a 4x price change results in a 20.0% loss relative to HODL”

- “a 5x price change results in a 25.5% loss relative to HODL”

“N.B. The loss is the same whichever direction the price change occurs in (i.e. a doubling in price results in the same loss as a halving).” —>